In our view, allocating capital is one of management’s most important responsibilities. There are several ways management can allocate the capital a company generates, including mergers and acquisitions (M&A), capital expenditures (money allocated by a business or organization for the acquisition or maintenance of fixed assets, such as land, buildings, and equipment) and research and development. Instead of allocating capital to grow the business, companies can also choose to return cash to shareholders via share repurchase and dividends. We have shared our concerns about the high levels of buyback activity and the related implications on several occasions in the past (See “Thoughts on Share Repurchase Activity Levels,” “Dividends vs. Stock Repurchase,” “Financial Engineering and Share Repurchases,” and “Greed in the Executive Suite.”).

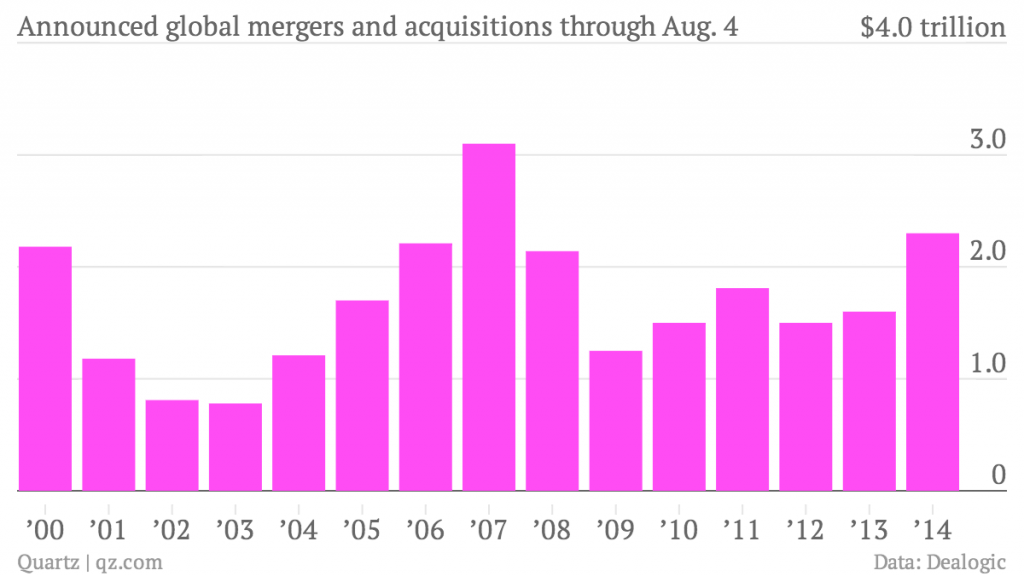

Corporate merger and acquisition activity has also been on the rise. As depicted below, according to Dealogic, through August 4, announced global M&A activity had reached its highest level for a single year since 2007. This figure has continued to expand, as according to data compiled by Bloomberg there have been $3.6 trillion of deals announced year-to-date. Note that of these, approximately $500 billion have been withdrawn or terminated.

At the right price, acquisitions can benefit business performance and lead to an increased stock price. When another company is purchased, synergies can lower the costs associated with running the combined entity. Duplicative functions can be eliminated and operating efficiencies can be gained. However, for the deal to really benefit shareholders and add long-term value, the right price must be paid. Overpaying for another company is not all that different than overpaying when buying stocks. It can lead to the permanent destruction of capital. In a rising market, the risk of overpaying for an acquisition increases.

It is also important to understand the motives for the transaction. Some CEOs appear most interested in building their empire, or expanding business units, staffing levels and the dollar value of assets under their control, rather than developing and implementing ways to benefit shareholders. In his book “One Up On Wall Street,” legendary investor Peter Lynch coined the term “diworsification” to describe a business that diversified too widely. This increases the risk that the original business will be destroyed or that management time, energy and resources will diverted from the original investment.

In the 1980s, several US companies tried to diversify their operations by buying insurance businesses. For example, copy maker Xerox and steel maker Armco acquired insurance businesses. The performance of both companies was weighed down by these insurance businesses which lost considerable money for their acquirers.

In summary, it is important to remember that a good capital allocation process looks first at opportunities to invest in projects that are sufficiently likely to earn a return greater than the firm’s cost of capital. Such projects can include investment in new projects or expansion of existing businesses. M&A can be another means of growing the business. When evaluating companies for inclusion in client portfolios, BWFA assesses how management allocates capital as it relates to capital investments, M&A and returning cash to shareholders.