In July and August of each year, most public companies report their second-quarter earnings. If you read or listen to media reports discussing the quarter’s results, you will likely find commentary discussing whether or not results exceeded analyst consensus estimates. Oftentimes, a company’s stock price will rise or fall on “good” or “bad” earnings as well. The question to ask is “Should we place much importance on earnings surprises?”

According to figures compiled by Yardeni Research (YR), through August 5, 404 companies in the S&P 500 had reported their quarterly results. Of these 70.5% had reported positive surprises (results surpassing analyst expectations) and 21.5% had delivered negative surprises (performance fell short of the consensus). Earnings for the remaining 7% were in line with forecasts. On the surface, that sounds like a pretty good outcome. If we look more closely, we will see that this result is somewhat typical.

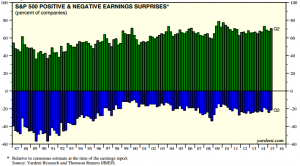

According to other data compiled by YR, since 2009’s first quarter no fewer than 62.7% of the companies in the S&P 500 reported earnings that surpassed expectations; at the same time, no more than 25.5% of results fell short of forecasted earnings. These results are not that far out of line with longer term results. As the chart shows, since the mid-1990s, it has been rare for more than 25% of companies in the S&P 500 to report negative earnings surprises.

It is important to note how difficult it can be to predict how much a company will earn in any given quarter or year. The models analysts generally use to map out their vision of a company’s future performance are largely based on the guidance given by companies when they release each quarter’s earnings. There are some companies like Warrant Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway that simply do not provide earnings guidance. However, the vast majority of companies provide some type of guidance. Analysts then input the information they get from management into their models so they can forecast results.

It is important to keep in mind that stock prices are more likely to rise on a positive surprise and fall on a negative one. To a certain extent, this makes earnings season somewhat akin to a game: Management teams often provide conservative guidance, increasing the odds that actual results will exceed expectations. However, if the quarter is not going well, or the consensus forecast looks too high, management may “warn” that earnings will be weaker than expected. Alternatively, other news during the quarter could also cause analyst outlooks to weaken.

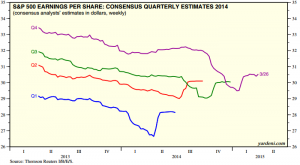

As a result, as the quarter progresses, analyst quarterly estimates are likely to fall. This tendency can be seen in the following chart from 2014 which shows that analyst estimates tend to move lower during the quarter – the hook up and to the right followed by the flattening of the line at the end of each quarter depicts actual results.

For long-term investors, whether or not a single quarter’s results meet or exceed the Wall Street consensus is not very relevant. What matters more is the strength of the company’s underlying business. Quarterly reports can provide valuable insight into the direction a business is going. However, worse-than-expected results do not necessarily mean it is time to rush for the exits. Just like companies, all of us have had bad quarters in our personal lives. A bad quarter does not mean that we (or the companies we own) are doomed to continue declining quarter after quarter. Whether earnings exceed, meet or fall short of expectations, the most important thing is to check in periodically on our companies and make sure that the valuation is reasonable and the investment thesis still holds.