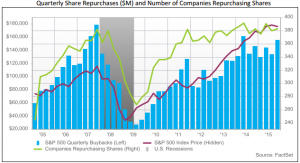

Over the past few years, many U.S. companies have borrowed heavily. However, many companies have used these funds to repurchase their shares instead of investing them to spur future growth. According to FactSet, the dollar value of share repurchases amounted to $156 billion in the third quarter (August-October), a 16% increase versus the second quarter (May-July) and a 6.4% year-over-year increase. Such activity shows no signs of abating, as through February 10, companies in the S&P 500 have announced $99 billion in buyback plans, marking the strongest start ever to a year.

Share repurchase activity has been a frequent topic of discussion in our weekly commentaries. (See one, two, three, four and five.) When a company’s stock is undervalued, stock buybacks can represent a perfectly good use of funds. However, our concerns center on three primary issues: (1) we want to invest in companies that allocate capital well; (2) share repurchase activity can represent a form of financial engineering; and (3) we want to see companies in our clients’ portfolios invest for future growth.

As investors, if we overpay for a stock, we will suffer losses. While it is not reflected on a company’s income statement, buying back shares that subsequently trade at a cheaper price represents a loss for companies as well. Recently, FactSet performed a study for the Seattle Times of the results of buyback activity by the members of the S&P 500. It found that, “The companies showing paper losses on these bets are down a collective $126 billion over the past three years, a decline of 15% during a time when the overall market rose 39%.” Importantly, it is not just a few big companies that have generated all these losses. Nearly half of the S&P’s constituents (229 companies) have lost money on share buybacks. In other words, it would have been better for shareholders if these companies had simply distributed these funds as dividends.

If a company repurchases its own shares, it lowers its share count, which results in higher earnings per share. This is why such activity can be considered a form of financial engineering. According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, without the reductions in shares outstanding over the last three years, S&P 500 earnings per share for 2015’s fourth quarter would have been 2% lower than what has actually been reported.

The low-interest-rate environment has made it easier for companies to borrow. According to the Federal Reserve, nonfinancial corporations owed $8 trillion in debt in 2015’s third quarter, up from $6.6 trillion three years earlier. The low-growth environment has also caused companies to buy back more shares, as the returns from investing in business expansion are less attractive than they were in the past.

However, this situation also has a negative side. Paying down debt may also be more challenging in a low-growth environment. If companies have not invested in future growth, their future cash flows will also be lower, leaving less money available to service debt. Many companies have refinanced debt to longer maturities, so the problem may not be immediate. But, it could represent a long-term earnings drag.

One way companies could overcome any shortfalls would be to issue new shares. However, that would dilute existing investors and serve as a further drag on earnings per share. It would be even worse if the shares were re-issued at lower prices than was paid for the shares the companies acquired.

It is also important to keep in mind that while many companies have large cash balances that they could use to repay debts, in many cases this cash is overseas. As a result, there could be a cost associated with repatriating the money to the U.S. so that it can be used to repay debts.

When reviewing companies that are held or that could be added to client portfolios, BWFA reviews share buyback activity as well as the amount invested in future growth opportunities. These are critical elements of management’s capital allocation policy. Effective capital allocation is an important element of our stock selection process.