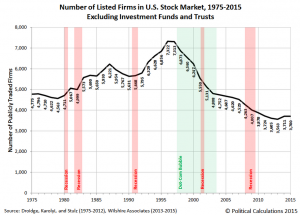

The number of publicly listed companies trading on U.S. exchanges has fallen by nearly half from its 1996 peak. In fact, since then, it has fallen in every year except 2014.

In May, Craig Doidge, G. Andrew Karolyi and René Stulze published a paper suggesting a number of reasons for the decline. Their paper cited two primary factors:

- An increasing number of startups are reluctant to go public.

- Many firms are delisting or going private and by removing their securities from from the exchange on which they trade.)

According to their research, delistings accounted for about 46% of the decline. The relative paucity of new listings accounted for the other 54%.

The authors found that the number of U.S. “new” listings fell from 8,025 in 1996 to 4,101 (49% decrease) in 2012. This trend was largely restricted to the U.S. as the number of non-U.S. listings rose from 30,734 to 39,427 (28% increase).

The researchers determined that a lack of startups or company formations was not the cause. In the U.S., the total number of new businesses was relatively unchanged, and the number of startups actually increased. A single industry – or a handful of them – was not responsible either. The authors noted that “listings decreased in all but one of the 49 industries after 1996.”

The study also reviewed the old argument that “regulatory and legal changes in 2000 including Regulation Fair Disclosure (‘Reg FD’) and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (‘SOX’) made it more costly to list. They determined that these had little-to-no impact, since the decline in listings was “well on its way before these changes took place.”

As for the delistings, they were driven by three primary factors:

- Mergers and acquisitions (M&A);

- Failure to meet listing requirements; and

- Going private.

M&A were a large source of delistings. The researchers found that from 1996 to 2012, nearly 45% of the delistings were due to mergers.

So, why did the number of startups going public begin to decline in 1996? and why did the share of post-M&A delistings climb? We can only venture some educated guesses.

It is notable that the timing of the increase in M&A activity largely coincided with the IT-driven productivity enhancements of the late 1990s. This could have lowered the cost of remaining a viable startup for a longer period than was previously thought possible. Plus, one of the drivers behind M&A activity is the push to lower costs.

It is also likely that companies need less capital to operate. Most firms go public when they get large enough that their demand for capital can only be met by going to the public markets. Since 2000, particularly in the U.S., the most valuable new firms are less heavily dependent on technology to run their operations. They also need to carry less inventory and build fewer manufacturing facilities. These factors lower capital requirements.

The availability of cheap capital may also play a role. Access to cheap capital can make venture capitalists more willing to invest in risky startups and more willing to wait for their businesses to become more mature. Additionally, mutual funds have also been writing big checks for startups before they go public. The billions of dollars they provide are largely behind the skyrocketing valuations of companies such as Uber, which allows them to stay private longer and garner a higher valuation if they ultimately go public.

At BWFA, a portion of client portfolios may be allocated to companies with the potential to deliver stronger growth (we classify such companies as “aggressive growth” (AG) in our models). Trends such as those cited above are making it harder to identify small companies capable of achieving above-average growth that meet our investment criteria. The end result is that we find it harder to identify small-cap stocks in which we want to invest. Instead, we have included some mid- and large-cap companies in our AG stock allocation.