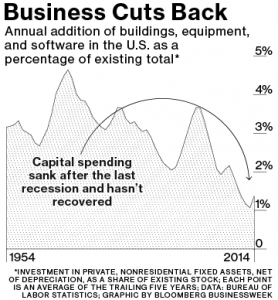

Although the U.S. economy has been in expansion mode for much of the last seven plus years, U.S. businesses are spending less on buildings, equipment and software than they have historically.

The data tells us that companies are reducing their capital expenditure budgets. However, it does not tell us what is driving this trend. When we discussed this topic last summer, we attributed at least some of the shortfall to greater investment in intangible assets, such as research, skills and patents. We also noted that companies are increasingly willing to outsource key functions. For example, many computer-related processes are maintained in the cloud. More recently, we also wrote about the tendency of younger generations to favor experiences over things.

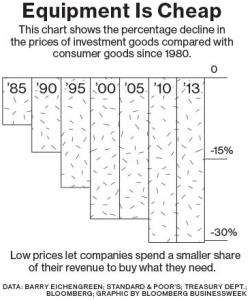

But, there are likely other factors at play. For example, as shown below, the cost of equipment has fallen. Lower prices allow companies to spend less and get more.

In addition, for more than a decade, the economy’s rate of productivity growth has been weak. This negatively impacts workers, as it keeps their incomes from rising quickly (or, perhaps, at all). In light of the increased reliance on information technology innovations that make our lives easier, such as iPhones, Google and Uber[i], one would think that we would be able to work more productively. This should either lead to more leisure time or enable us to get more done at work and earn more money. At the same time, lower income can suppress demand.

A number of people have posited that government statisticians must be missing something in the way they measure the economy – such as, the benefits of Google and all the free things we can access on our computers, tablets and phones. Our phones come with apps that allow us to drive nearly everywhere without using maps or buying a GPS. Our children and grandchildren no longer need to use encyclopedias or take trips to the library to perform research. They can usually find whatever information they need on the internet. Most people also use their phones to take pictures, so they no longer have to buy separate cameras.

Recently, Fed economists released a research paper refuting the idea that the availability of so much free stuff is having a negative impact on growth and productivity. Their primary argument is that free services like Facebook or Twitter should not be reflected in gross domestic product (GDP) or in productivity measures, since consumers do not pay for these services directly. Instead, the costs of providing them are paid for by advertisers. The authors argue that the concept of consumers being able to see things for free because advertisers pay the costs has been around for decades. For example, television broadcasting was free to households when it was introduced. While we typically pay to bring a signal into our homes, we are still not paying most of the companies that generate the content we watch.

The Fed authors see free services such as Google as a form of “consumer surplus” or the value consumers place on goods they buy that is over and above the price they paid. This surplus has never been included when measuring productivity or GDP in the past. At the same time, doing things with fewer inputs represents a form of growth. The internet is enabling new, sometimes more efficient ways of sharing and collaborating, which do represent some generally modest growth. There is not a new, separate “collaborative economy.”

We expect these trends to continue. The Internet of Things, further developments in artificial intelligence, autonomous cars and the sharing economy will continue to “disrupt” the economy. Going forward, these technologies will improve our quality of life and increase the importance of intangibles in our lives. They will also require less in the way of material inputs and increase the efficiency of the way things are used.

It seems likely to us that economic growth is being underestimated as we are using old systems and methodologies to measure growth in a world that has changed considerably from when these figures were first calculated. At the same time, the increased reliance on intangible assets makes it harder to estimate the value of companies as well as their contribution to economic growth. The fundamental analysis we perform is designed to help us identify those companies that are best positioned to survive and thrive.

[i] Apple (manufactures iPhones) and Alphabet (parent company of Google) are currently on BWFA’s “Buy/Hold” list of securities and may be held in client portfolios.