What is capital gains tax? Capital gains tax is imposed on gains realized from the sale of capital assets such as a home, an investment, or a business interest.

Special maximum tax rates generally apply to long-term capital gains; these rates are typically lower than the rates that apply to ordinary income. These special maximum rates also generally apply to qualified dividends.

CAPITAL GAINS TAX ON SALE OR EXCHANGE OF CAPITAL ASSETS

If you sell or exchange a capital asset for more than its basis (cost), the profit is a capital gain. If you sell or exchange a capital asset at a loss, you can generally use the loss to offset capital gains (subject to the netting rules, discussed below). If your capital losses exceed your gains, you can offset a certain amount of ordinary income and/or carry the loss forward into future tax years.

The tax rate that will apply to the sale or exchange of a capital asset depends on a number of factors, including the type of asset, how long you owned (held) the asset, and your taxable income.

TIP: Under the homesale exclusion, gain on the sale of your principal residence (up to certain limits) can be excluded from income, as long as certain conditions are met.

CAUTION: Generally, loss resulting from the sale or exchange of personal property is not deductible. A loss on the sale or exchange of property between related parties is also generally not deductible.

WHAT IS A CAPITAL ASSET?

Just about everything you own and use for personal purposes or for investment purposes is a capital asset. However, capital assets do not include:

- Inventory, stock in trade, or property held primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course of your trade or business

- Depreciable or real property used in your trade or business

- Certain literary or artistic property

- Business accounts or notes receivable

- Certain U.S. publications

- Certain commodity derivative financial instruments

- Hedging transactions

- Business supplies

CAUTION: When you sell or dispose of business property, special rules apply under IRC Section 1231 in determining whether taxable gain is treated as ordinary gain or capital gain. When you sell or dispose of depreciable property, special rules under IRC Sections 1245 and 1250 may also apply. For more information, see IRS Publication 544, Sales and Other Dispositions of Assets.

HOLDING PERIOD

Holding period refers to the length of time you held a capital asset before selling or exchanging it. A gain is classified as short-term if you held the asset for a year or less before selling it, and long-term if the asset was held for longer than a year. This distinction is important because net short-term capital gains are taxed at ordinary income rates, whereas long-term capital gains are taxed at the more favorable long-term capital gains tax rates.

HOW DO CAPITAL GAINS TAX RATES DIFFER FROM ORDINARY INCOME TAX RATES?

Capital gain income is generally preferable to ordinary income. Currently, the highest marginal income tax rate is 37 percent, while long-term capital gains tax rates vary from 0 percent to 28 percent, depending on the asset and your taxable income. Generally, current long-term capital gains tax rates can be grouped as follows:

- 28 percent for collectibles and small business stock

- 25 percent for unrecaptured IRC Section 1250 gain

- 0 percent, 15 percent, and 20 percent for most long-term capital gains and qualified dividends, depending on your taxable income. The actual process of calculating tax on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends is extremely complicated and depends on the amount of your net capital gains and qualified dividends and your taxable income.

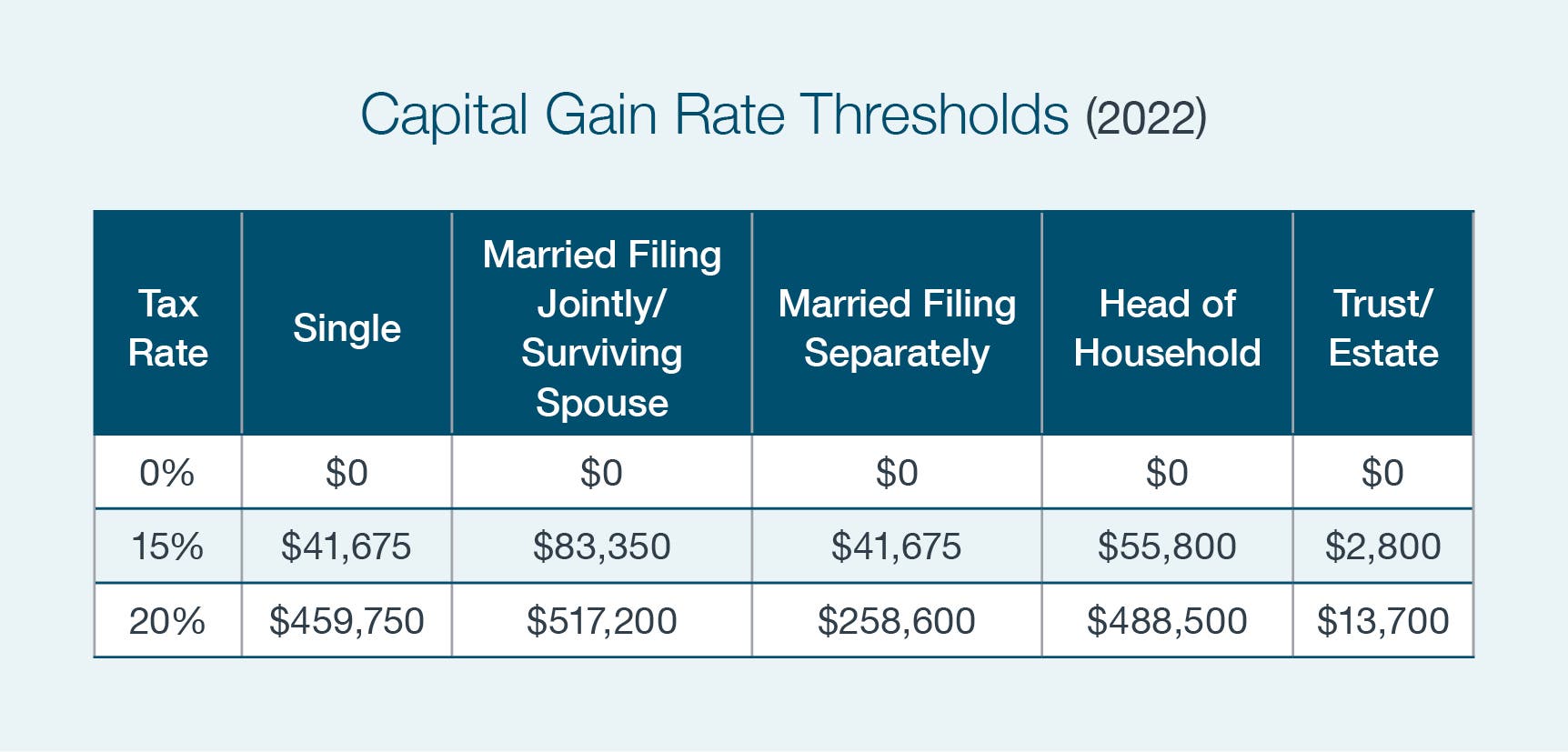

The following table can help you estimate which of the 0 percent, 15 percent, or 20 percent capital gain tax rates applies to your long-term capital gains and qualified dividends.

A dividend is the distribution of property made by a corporation to its shareholders out of its after-tax earnings and profits. Qualified dividends are taxed at the same rates that apply to net capital gain.

If you don’t have any 25 percent or 28 percent capital gains, you generally allocate your net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends against your highest taxable income as shown in the following examples.

EXAMPLE: Assume Mary has taxable income that is $15,000 greater than her capital gains rate threshold for 15 percent and has net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (net capital gain) of $20,000 (none of which is 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain). $5,000 of her net capital gain is taxed at 0 percent, and $15,000 is taxed at 15 percent.

EXAMPLE: Assume Dave and Ann have taxable income that is $150,000 greater than their capital gains rate threshold for 15 percent and have net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (net capital gain) of $80,000 (none of which is 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain). All of their net capital gain is taxed at 15 percent.

EXAMPLE: Assume Tom has taxable income that is $40,000 greater than his capital gains rate threshold for 20 percent and has net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (net capital gain) of $100,000 (none of which is 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain). $60,000 of his net capital gain is taxed at 15 percent, and $40,000 is taxed at 20 percent.

EXAMPLE: Assume a trust has taxable income that is $40,000 greater than its capital gains rate threshold for 20 percent and all of it is net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (net capital gain) (none of which is 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain). A portion of the net capital gain is taxed at 0 percent, a portion is taxed at 15 percent, and $40,000 is taxed at 20 percent.

If you have 28 percent or 25 percent capital gains, you generally allocate them, in that order, against your highest taxable income. Then you allocate your remaining net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends against your next highest taxable income.

EXAMPLE: Assume Mary has taxable income that is $15,000 greater than her capital gains rate threshold for 15 percent and has net long-term capital gains and qualified dividends (net capital gain) of $20,000 ($3,000 of which is 25 percent capital gain, and $2,000 of which is 28 percent capital gain). Of the $15,000 net capital gain that is other than 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain, $5,000 is taxed at 0 percent, and $10,000 is taxed at 15 percent.

The examples show a relatively simple way to estimate what capital gain tax rates could apply. As noted, the actual process of calculating tax on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends is extremely complicated, as evidenced by a couple of IRS worksheets for determining the tax on capital gains and qualified dividends. If you don’t have 28 percent or 25 percent capital gains, you can generally use the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet in the instructions for IRS Form 1040, U.S. Individual Tax Return. If you have 28 percent or 25 percent capital gains, you can use the Schedule D Tax Worksheet in the instructions for schedule D of IRS Form 1040.

Capital losses are netted against capital gains. Up to $3,000 in excess capital losses is deduct-ible against ordinary income each year. Unused net capital losses are carried forward indefinitely and may offset capital gains, plus up to $3,000 of ordinary income during each subsequent year.

If your capital gain in a given year pushes you into a higher capital gain tax bracket, which capital gain rate do you use?

Suppose you are normally in the 0 percent capital gain tax bracket, but in December of this year, you sell an asset held for two years and realize a substantial long-term capital gain. Will the full capital gain be untaxed because of the 0 percent rate? Maybe not. If your capital gain pushes you into a higher capital gains tax bracket, you can use a preferred capital gains tax rate of 0 percent on a portion of the capital gain only. The remainder of your capital gain will be taxed at the higher 15 percent rate.

EXAMPLE: Assume John has taxable income that is $10,000 less than his capital gains rate threshold for 15 percent. He realizes a long-term capital gain of $40,000 (which is not 25 percent or 28 percent capital gain) and his taxable income increases to $30,000 greater than his capital gains rate threshold for 15 percent. $10,000 of his net capital gain is taxed at 0 percent, and $30,000 is taxed at 15 percent.

It is possible for individuals with substantial long-term capital gains to still benefit in some degree from the 0 percent rate. This will generally be true, however, only in cases where long-term capital gains make up a significant portion of taxable income.

WHAT ARE THE NETTING RULES?

In order to properly compute your capital gains tax, you should be aware of the manner in which capital gains and losses may offset one another. These rules are known as the “netting rules.” Generally speaking, the tax code prescribes that short-term capital gains and losses must be netted against each other first. Next, long-term capital gains and losses are netted against one another according to a set of ordering rules. Finally, net short-term gains or losses must be netted against net long-term gains or losses in a prescribed manner.

The ordering rules apply if you have long-term capital gains that are subject to different rates of tax. With respect to long-term capital gains and losses, the following rules apply:

- Long-term gains and losses are first grouped into three buckets: the 28 percent group, the 25 percent group, and a group for all other long-term capital gains (i.e., long-term capital gains to which the 0 percent, 15 percent, or 20 percent rates will apply).

- Losses for each long-term tax rate group are used to offset gains within the group, resulting in a net long-term gain or loss for each group.

- If a net short-term capital loss exists, it reduces net long-term gain from the 28 percent group first, then from the 25 percent group, and finally from remaining gains.

- A net loss from the 28 percent group is used first to reduce gain from the 25 percent group, then to reduce net gain from remaining gains. And a net loss from the 0 percent/15 percent/20 percent group is used first to reduce net gain from the 28 percent group and then to reduce gain from the 25 percent group.

- Any remaining net capital gain in a particular rate group is taxed at that group’s associated rate.

NET CAPITAL LOSSES

Capital losses are netted against capital gains. Up to $3,000 in excess capital losses is deductible against ordinary income each year. Unused net capital losses are carried forward indefinitely and may offset capital gains, plus up to $3,000 of ordinary income during each subsequent year. (The $3,000 limit is reduced to $1,500 for married persons filing separately.)

EXAMPLE: Assume Jane has a short-term capital gain of $1,200 and a short-term capital loss of $1,300, resulting in a net short-term capital loss of $100. She also has a net long-term capital gain of $600 and a net long-term capital loss of $4,200, resulting in a net long-term capital loss of $3,600. The excess of Jane’s capital losses over capital gains is $3,700 ($100 + $3,600). This excess is deductible from ordinary income up to a maximum of $3,000 this year; the remainder may be carried over to future years.

When you carry over a loss, it retains its original character as either long-term or short-term (e.g., a short-term loss you carry over to the next tax year is added to short-term losses occurring in that year, and a long-term loss you carry over is added to long-term losses occurring in that year). A long-term capital loss you carry over to the next year reduces that year’s long-term gains before its short-term gains. If you have both short-term and long-term losses, short-term losses get used first in calculating your allowable loss deduction.

CONSIDERATIONS

Time your capital gain recognition. Careful planning may save you taxes. For example, because capital gain or loss is not recognized for federal income tax purposes until you dispose of an asset, in many cases you have some control over the timing of recognition. If you believe that you will be in a lower tax bracket next year, you can choose to post-pone the sale of a capital asset to defer recognition of gain or loss until that year.

Plan your year-end capital gain and loss status. If you realize a capital gain this year, you should consider reviewing your portfolio for potential losses, and decide whether it makes sense to recognize losses to offset your gain. Remember also that you can use up to $3,000 ($1,500 if married filing separately) worth of losses (if applicable) to offset ordinary income.

Similarly, if you have a capital loss this year (or have a capital loss carryforward), you should review your portfolio for potential gains for offset purposes. This may help to lower your overall tax liability.

For property held as an investment, elect to include gain in investment income. You may elect to treat capital gains from investment property as investment income instead. If such an election is made, gains will be taxed at ordinary rates and can be used to offset investment interest expenses. This may be advantageous for individuals who have sufficient capital losses to offset capital gains, and insufficient investment income to offset investment interest expenses (remember that investment interest expenses can only be used to offset investment income, although they can be carried forward and used in future tax years).

Holding period refers to the length of time you held a capital asset before selling or exchanging it. A gain is classified as short-term if you held the asset for a year or less before selling it, and long-term if the asset was held for longer than a year. This distinction is important because net short-term capital gains are taxed at ordinary income rates, whereas long-term capital gains are taxed at the more favorable long-term capital gains tax rates.

QUALIFIED DIVIDENDS

A dividend is the distribution of property made by a corporation to its shareholders out of its after-tax earnings and profits. Qualified dividends are taxed at the same rates that apply to net capital gain.

What are qualified dividends? Qualified dividend income generally includes dividends received from domestic corporations and qualified foreign corporations.

A qualified foreign corporation includes any foreign corporation incorporated in a possession of the United States, as well as any foreign corporation that is eligible for the benefits of a comprehensive income tax treaty with the United States, determined to be satisfactory and which includes an exchange of information program.

In addition, a foreign corporation is treated as a qualified foreign corporation for any dividend paid by the corporation with respect to stock that is readily tradable on an established securities market in the United States.

Qualified dividends do not include:

- Any dividend, to the extent that you are obligated (e.g., pursuant to a short sale) to make related payments with respect to positions in substantially similar or related property

- Any amount you elect to take into account as investment income

- Any amount allowed as a deduction under IRC Section 591 (relating to deduction for dividends paid by mutual savings banks, etc.)

In addition, special rules and limitations apply to dividends received from regulated investment companies and real estate investment trusts (REITs).

Holding period requirement. If you do not hold a share of stock for more than 60 days during the 121-day period beginning 60 days before the ex-dividend date, dividends received on the stock are not eligible for the reduced rates.

In the case of preferred stock dividends attributable to a period or periods which in aggregate exceed 366 days, the holding period requirement is more than 90 days during the 181 day-period beginning 90 days prior to the ex-dividend date.

Relationship to capital gains. For purposes of calculating federal income tax, qualified dividends are taxed at the same maximum rates that generally apply to long-term capital gains. For this purpose only, they are added to net capital gain and adjusted net capital gain in the capital gain tax calculation. However, qualified dividends are not netted against capital gains and losses, and capital losses cannot be used to offset qualified dividend income.

Qualified dividends may be reported on Schedule D along with capital gains. If you do not file Schedule D, the IRS Form 1040 instructions provide a worksheet you can use to calculate the tax.

LAWRENCE M. POST

CPA, MST, CFP®, CIMA®

Senior Tax & Planning Advisor

lpost@bwfa.com